Wildfires are rapidly transforming parts of the Arctic once considered too cold and wet to burn extensively. From Alaska’s North Slope to the forests of Siberia and northern Canada, researchers are documenting a dramatic rise in fire activity, with consequences that extend far beyond the burned landscapes.

A Changing Arctic Fire Regime

The increase in Arctic wildfires is closely linked to warming temperatures. As permafrost, ground that has remained frozen for decades or centuries, begins to thaw, soils dry out and become more vulnerable to ignition. At the same time, Arctic vegetation is changing. Woody shrubs are expanding northward and replacing mosses and sedges, creating more flammable landscapes.

These combined changes are pushing parts of the Arctic into a new fire regime. What were once isolated fire events are becoming more frequent, longer-lasting, and more intense.

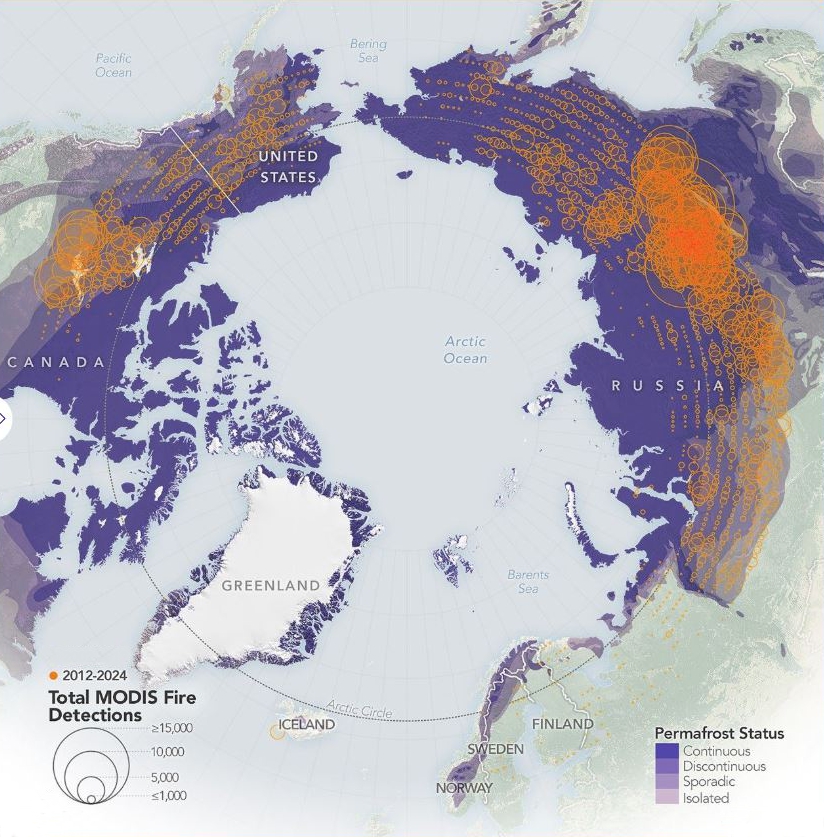

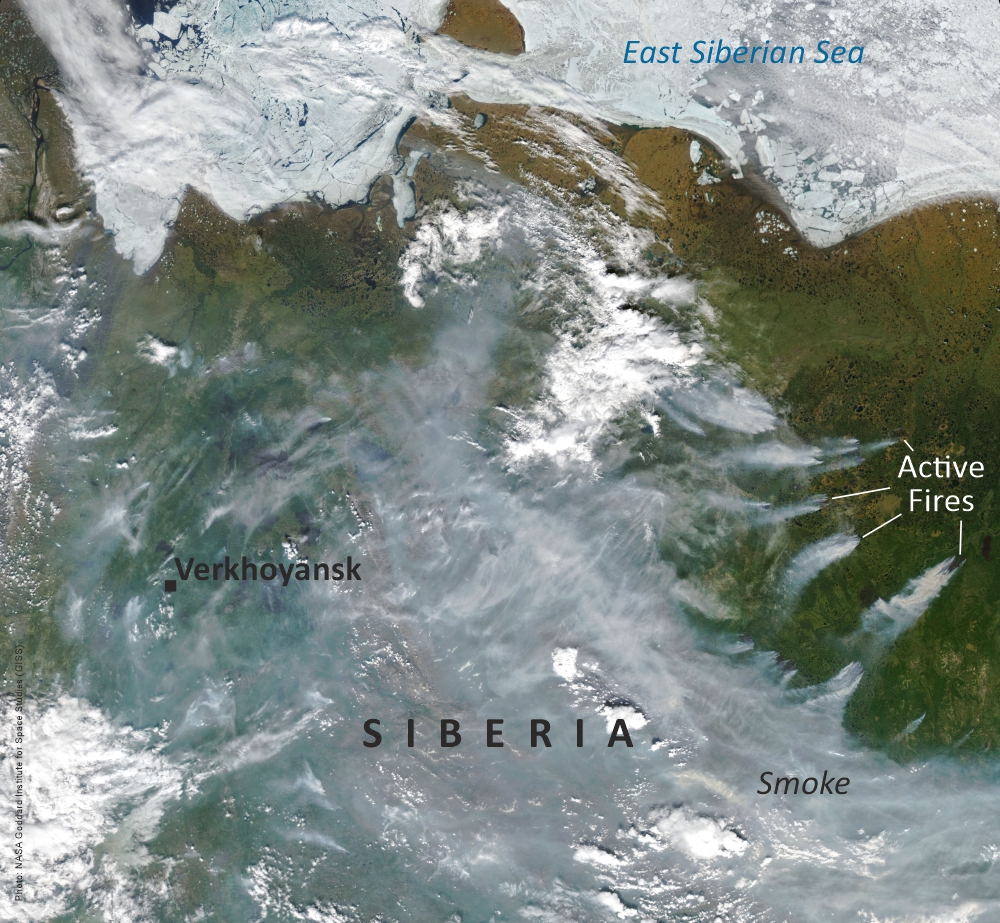

Similar trends are being observed across the circumpolar north. In Siberia, wildfire frequency and severity have increased markedly over the past two decades, with vast areas of boreal forest burning during extreme fire seasons. Satellite data indicate that fire activity in parts of central Siberia has roughly doubled in recent years. Northern Canada has also experienced record-breaking fire seasons, with widespread impacts on ecosystems and communities.

Similar trends are being observed across the circumpolar north. In Siberia, wildfire frequency and severity have increased markedly over the past two decades, with vast areas of boreal forest burning during extreme fire seasons. Satellite data indicate that fire activity in parts of central Siberia has roughly doubled in recent years. Northern Canada has also experienced record-breaking fire seasons, with widespread impacts on ecosystems and communities.

The Rise of “Zombie Fires”

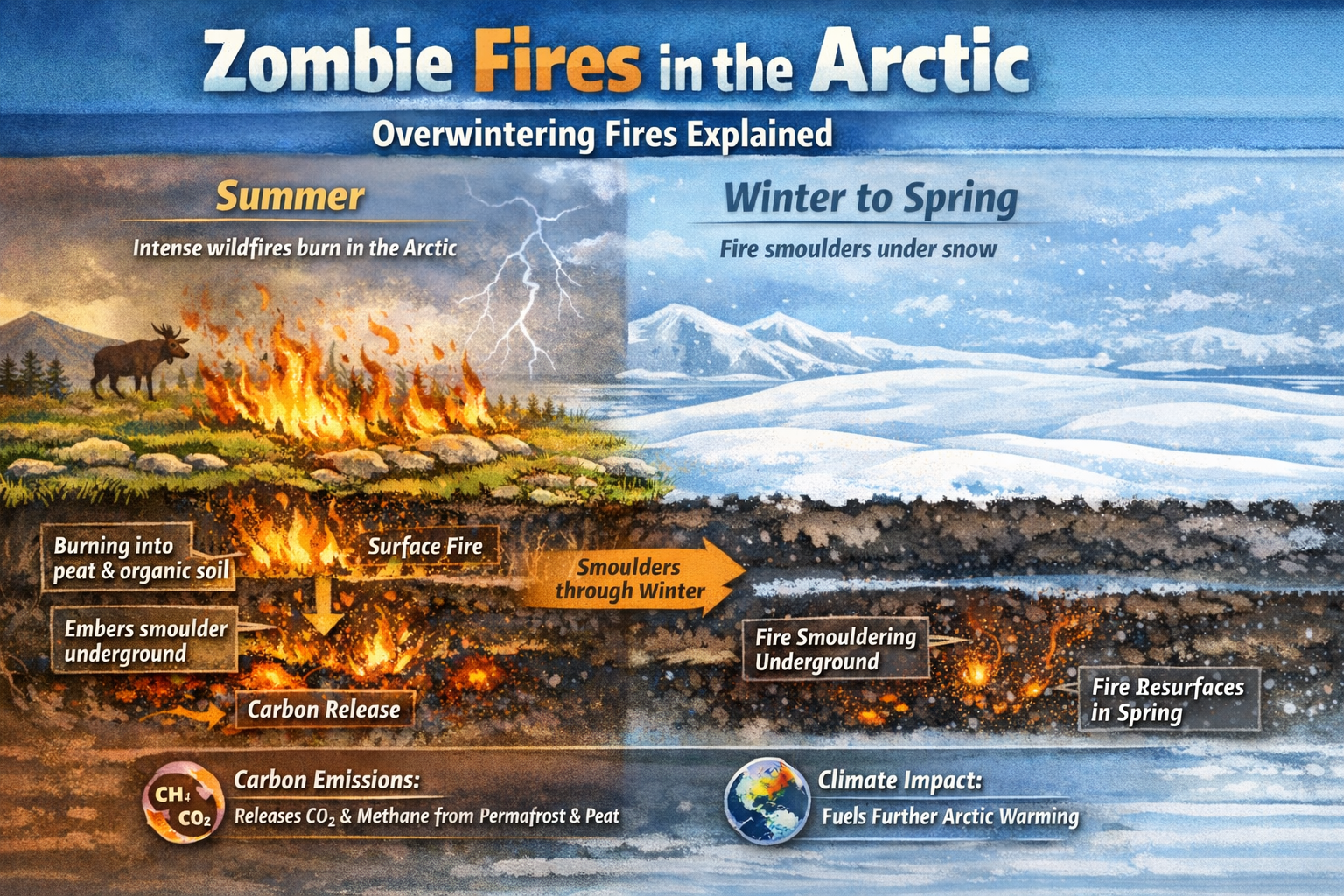

While most Arctic wildfires ignite during the summer months, when lightning strikes, dry vegetation, and warmer temperatures create ideal conditions, a new and troubling phenomenon has emerged: overwintering fires, often referred to as “zombie fires.”

Unlike typical surface fires, these events burn deep into organic-rich soils and peat layers. Instead of extinguishing completely when winter arrives, the fires can continue to smoulder underground at low temperatures. Insulated by snow cover, embers may survive for months beneath the surface.

Unlike typical surface fires, these events burn deep into organic-rich soils and peat layers. Instead of extinguishing completely when winter arrives, the fires can continue to smoulder underground at low temperatures. Insulated by snow cover, embers may survive for months beneath the surface.

When spring snow melts, the fire can reignite above ground, sometimes in the same location as the previous year’s burn.

Overwintering fires have been documented in Alaska, Siberia, and northern Canada. Although still relatively uncommon compared to conventional summer ignitions, scientists warn that their frequency may increase as Arctic summers become warmer and longer, and soils continue to dry.

Why Arctic Fires Are Especially Concerning

Why Arctic Fires Are Especially Concerning

Arctic landscapes store enormous amounts of carbon in frozen soils and peatlands. When fires burn into these layers, they release carbon dioxide and methane that have been locked away for centuries or even millennia. This release contributes to further atmospheric warming, creating a feedback loop: warmer temperatures lead to more fires, and more fires lead to greater greenhouse gas emissions.

Zombie fires are particularly difficult to detect and extinguish. Because they burn underground, they can evade traditional firefighting methods and monitoring systems. Their slow, persistent smouldering can also damage permafrost stability, alter hydrology, and transform vegetation patterns long after visible flames have disappeared.

Beyond climate impacts, Arctic wildfires affect biodiversity, wildlife habitats, air quality, and Indigenous communities that depend on the land for subsistence and cultural practices. Smoke from large fires can travel thousands of kilometers, influencing weather patterns and air conditions far beyond the Arctic region.

A New Arctic Reality

The growing intensity and persistence of wildfires suggest that the Arctic is entering a fundamentally different environmental state. Regions that historically experienced infrequent tundra fires are now facing regular burning. As scientists continue to monitor these changes, improved fire management strategies and long-term adaptation planning are becoming increasingly important across Arctic nations.

The rise of Arctic wildfires — including the emergence of overwintering “zombie fires” — highlights the complex and accelerating interactions between climate change, ecosystems, and carbon cycles in the far north.

Source: ScinceDaily, Wildfland Fire, ScienceDirect, Science Alert, Cornell University

Photos: NASA Earth Observatory, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS)